St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican

Contents

History

The Exterior of the Basilica

The Interior of the Basilica

St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican is a fundamental landmark for Catholicism and a masterpiece of Italian artistic heritage, poised to be a premier pilgrimage destination during the 2025 Jubilee in Rome. This extraordinary structure, in addition to being a symbol of faith and spirituality, represents an exceptional example of architecture with its imposing facade and Michelangelo's famous dome that dominates the city's skyline. The iconic St. Peter's Square, crafted by Bernini, will welcome thousands of pilgrims flocking to Rome to partake in the 2025 Jubilee celebrations, offering a perfect blend of art and faith in a majestic setting.

History

St. Peter's Basilica, one of the most significant symbols of Catholicism in Rome, represents an architectural and spiritual milestone whose history is marked by various phases of construction and restoration.

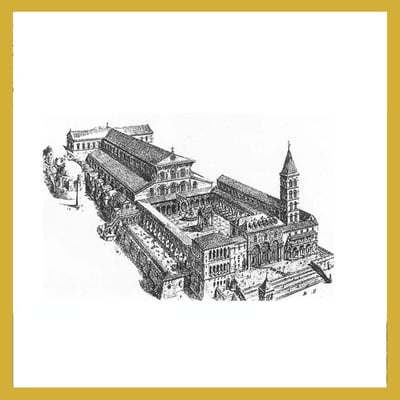

The Early Christian Basilica

The cornerstone of the original basilica was laid in 324 by Emperor Constantine I on what was believed to be the burial site of St. Peter. This venerable structure, finalized in 349, reflected the basilical style and was built to accommodate the numerous pilgrims who, since the early centuries, arrived to venerate the apostle's tomb. However, over the centuries, the building suffered damage and modifications, until a radical restoration was deemed necessary.

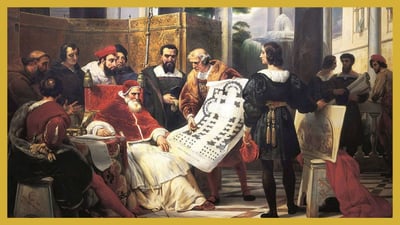

The Renewal by Julius II

The renewal of the basilica began under the pontificate of Pope Julius II in 1506 when he decided to demolish the old structure and commissioned Donato Bramante to design a building that reflected the rise of the Roman Renaissance. Bramante designed a grandiose central-plan structure, partly inspired by the Pantheon’s dome in Rome. Upon Bramante’s death in 1514, the project was subsequently entrusted to artists of the caliber of Raphael, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, and Michelangelo.

Michelangelo's Intervention

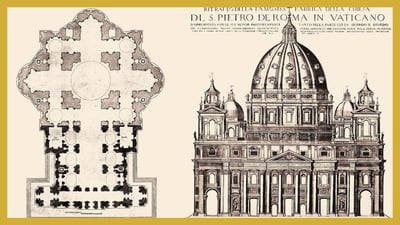

Michelangelo, who took over the project in 1547, made substantial changes to the original design, redesigning the dome and reinforcing the structure with more robust supports. The dome was completed posthumously in 1590, under the direction of Giacomo della Porta. At 132.5 meters high, it remains one of the most imposing structures in the urban landscape of Rome.

The Completion by Carlo Maderno

The final phase of the basilica’s completion began in 1607 under the guidance of Carlo Maderno, who extended the main nave to form a Latin cross, adding a Baroque facade that was completed in 1614. This modification not only increased the basilica’s capacity to host a larger number of faithful but also emphasized the longitudinal axis, contrasting with the original centrally planned design.

Bernini and the Square

Under Pope Alexander VII, Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed St. Peter’s Square between 1656 and 1667, creating a broad elliptical colonnade. This space not only functioned as a welcoming open arm for pilgrims approaching the basilica but also served to visually define the urban space as a sacred and communal meeting place.

The following phases of restoration and conservation have enabled the Basilica of Saint Peter to preserve its magnificence and spiritual significance across the ages. The Holy Door, opened exclusively during the Holy Year, remains a powerful symbol of renewal and redemption, visited by millions of pilgrims, particularly during the Jubilees, under the guidance of pontiffs including the current Pope Francis.

The Exterior of the Basilica

The exterior of St. Peter’s Basilica is an architectural masterpiece that reflects the artistic and religious transformations over the centuries. Located in the heart of Rome, its monumental structure commands the cityscape, each architectural detail rich with symbolic meaning and purpose.

The Facade

Completed in 1614 by Carlo Maderno, the facade of Saint Peter’s Basilica stands as a majestic introduction to the most pivotal religious edifice in Catholicism. Spanning approximately 115 meters in width and 45 meters in height, it features a colossal order of columns supporting a massive attic adorned with 13 travertine statues of Christ, Saint John the Baptist, and the eleven apostles, excluding Saint Peter, whose statue prominently graces the basilica's balustrade, accompanied by Saint Paul’s statue. These figures embody the Church's foundations and its global message.

At the heart of the facade lies the loggia of blessings, from which the Pope imparts words to the faithful during principal liturgical events, notably during the Jubilee and Holy Year. This loggia is also the venue for the announcement of a new pontiff and is where the Urbi et Orbi blessing is delivered by Pope Francis and his predecessors.

The Holy Door

Situated at the far right of the facade, the Holy Door of the Basilica is one of Rome's four holy doors. It is solemnly opened at the start of each Holy Year, symbolizing a new opportunity for redemption and forgiveness. With a ceremony of equal symbolism, it is sealed at the close of the Holy Year, staying closed until the next Jubilee, marking a period of intense reflection and spiritual renewal for the faithful.

Designed by Vico Consorti for the 1950 Jubilee, the Holy Door features 16 rectangular panels that depict the story of humanity from its origins to the present, organized into four sections containing 36 coats of arms.

The Dome

The construction of the dome began in 1547 under Michelangelo's supervision, who by then had attained significant artistic renown. Although earlier architects like Bramante and Sangallo had largely shaped the basilica's basic structure, it was Michelangelo who revolutionized the dome's concept with a design requiring avant-garde construction techniques.

Michelangelo designed the dome with an internal diameter of about 42 meters, which rivals the grandeur and scale of the Pantheon’s dome. His intent was to eclipse all existing domes, creating a visible symbol of spiritual and artistic ascendancy that elevated the heavens above Rome. St. Peter's dome is mounted atop a lofty drum, adorned with windows that bathe the interior in light, creating a dramatic and illuminating effect, symbolic of divine enlightenment.

Although Michelangelo did not live to see the dome completed, his blueprint was realized with minimal modifications by his successors. The dome reached completion in 1590, under the supervision of Giacomo della Porta and Domenico Fontana. Della Porta introduced significant alterations to Michelangelo's original design, elevating and tapering the dome for a more elongated profile, an adaptation that has defined the distinctive silhouette of the structure we observe today.

Above the drum, the dome ascends with an elegant curvature, segmented into panels adorned with mosaics of religious motifs, converging towards the central oculus. This internal structure is strengthened by radiating ribs, which support the weight of the monumental construction and distribute it across the drum and the robust underlying cornerstones.

The construction technique for the dome, incorporating materials such as travertine and specially lightweight bricks, represented the pinnacle of contemporary engineering and attests to the ingenuity of Renaissance architects and engineers. Each facet of the design was meticulously calculated to ensure that the dome was not only aesthetically majestic but also structurally sound, a daunting task given its impressive size and height.

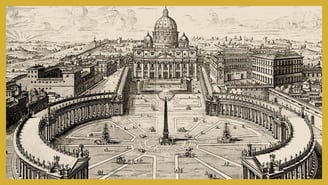

St. Peter's Square

Bernini envisioned the square as a grand 'maternal embrace' by the Church toward the faithful, visually symbolizing the welcome of pilgrims into the spiritual home of Christianity. The square is highlighted by a gigantic oval, encircled by a Doric colonnade of four rows of deep columns, creating a welcoming circular pathway leading towards the basilica. These columns are arranged to form a portico of 284 columns in total, crowned by 140 statues of saints crafted by various sculptors from Bernini’s era. This setup not only enhances the sense of community and inclusivity but also elevates the square to a space of celebration and veneration.

At the center of the square stands an ancient Egyptian obelisk, transported to Rome in 37 AD under Emperor Caligula and placed centrally by Domenico Fontana by the decree of Pope Sixtus V in 1586. The obelisk, encircled by a stone rosette symbolizing the winds, is not merely a visual focal point but also serves as a solar symbol, bridging the eras of the pharaohs with that of the popes. Flanked by two magnificent fountains by Carlo Maderno (1613) and Bernini himself (1675), the obelisk also functions as a sundial, with its shadow tracing the designs on the square.

The elliptical design of the square was conceived to elevate the sense of hospitality and accentuate the visual impact of the basilica when seen from the main entrance. Bernini employed techniques of forced perspective to make the basilica appear nearer than it really is, creating a visual illusion that heightens the emotional impact on those entering the square.

Symbolically, the square is a sacred space where heaven and earth converge, with the basilica serving as a conduit between humans and the divine. During Jubilee celebrations, it transforms into a gathering spot for prayer and festivities, underscoring its significance not merely as a physical location but as a pivotal liturgical venue in the Church's life.

The Interior of the Basilica

St. Peter's Basilica in Rome reveals itself as an architectural jewel, epitomizing the grandeur and splendor of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. This sacred space is crafted to awe, uplift the spirit, and manifest the Church's magnificence, presenting itself as a meticulous piece of architectural artistry..

Interior Panorama

The expansive inner domain is governed by a central nave that guides the eyes and spirit toward the high altar, crowned by Bernini's Baldacchino, a nearly 100-foot tall bronze structure erected between 1624 and 1633. The Baldacchino's twisted columns not only fortify the structure but are richly festooned with symbols of the Barberini family, articulating the ties between the basilica and the popes pivotal in its development and restoration.

The space's geometry is further highlighted by the dimensions of the main nave, 82 feet in breadth and 151 feet in height, stretching some 692 feet to the grandiose apse. This apse is framed by an expansive mosaic—one of many adorning the basilica's ceiling—depicting scenes from Christian tradition with technical finesse that captures the natural light streaming through myriad windows.

The basilica's internal architecture bursts with ornamental nuances, including golden stuccos, multicolored marbles, and intricate sculptures that augment the architectural forms, imparting a divine lushness. Each element, from the robust marble columns sustaining the framework to the various minor altars along the side aisles, is crafted to enrich the visual and spiritual narrative that St. Peter's Basilica so compellingly tells.

The Baldacchino of St. Peter

Gian Lorenzo Bernini's Baldacchino of St. Peter stands as one of the most iconic features within St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Poised precisely over the tomb of the apostle Peter, this imposing Baroque canopy is not only an artistic wonder but also a potent symbol of religious and historical significance.

Constructed from 1624 to 1633 during the tenure of Pope Urban VIII, Bernini's Baldacchino was his inaugural major contribution to the Basilica. This commission occurred at a time when the Catholic Church, through its art and architecture, aimed to affirm its influence and stature in reaction to the Protestant Reformation. Towering at nearly 100 feet, the Baldacchino commands the basilica's main altar and serves as a visual anchor that merges the heavenly quality of the dome above with the sanctity of the site it overshadows.

This blend of historical resonance and artistic scale in Bernini's work not only dominates the visual landscape but also symbolizes the Catholic Church's enduring cultural and spiritual authority. Moreover, the overwhelming artistry and architectural sophistication invoke a profound reflection on the Church's historical and theological roots, ensuring that every visitor to St. Peter's Basilica experiences a palpable sense of awe and reverence.

The design of the Baldacchino incorporates four colossal spiral columns, inspired by the Solomonic columns traditionally used in Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. These columns not only create a strong visual impact but are also laden with symbolism: their spirals can be seen as a nod to the ascent toward the divine. Each column is embellished with vine leaves and bees, symbols found in the Barberini family crest, thereby highlighting the patronage of Pope Urban VIII, who belonged to this family.

The upper portion of the Baldacchino is crowned with an ornate gilded bronze canopy, featuring ornamental volutes that support a globe and a cross, emblematic of Christ's dominion over the world. The angels and cherubim that adorn the canopy add further layers of artistic intricacy and theological significance, underscoring its role as a sacred marker atop the tomb of the Apostle Peter.

Michelangelo's Pietà

Michelangelo's Pietà, housed within St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, is heralded as one of the most revered and profound sculptures of the Renaissance. Created between 1498 and 1499, when Michelangelo Buonarroti was just 24 years old, this remarkable artwork is his only signed piece, proudly marked across the Virgin Mary's chest.

Situated near the basilica's entrance, the Pietà offers a poignantly dramatic portrayal of the Madonna cradling the lifeless body of Christ post-crucifixion. The composition showcases Michelangelo’s meticulous attention to detail and his masterful sculpting skills, evoking a deep sense of compassion and mourning. Michelangelo challenges the artistic norms of his era by depicting an unusually youthful Mary, symbolizing her purity and eternal youth, diverging from traditional, older depictions.

This representation of the Virgin Mary and Christ is not solely an artistic choice but is also fraught with theological implications, mirroring contemplations on both human and divine suffering. The sculpture gains additional layers of meaning in the context of the Jubilee, when pilgrims worldwide visit St. Peter's Basilica to meditate on themes of redemption, sacrifice, and mercy, which are central to the iconography of the Pietà.

Over the centuries, the sculpture has undergone various restorations, the most notable following a vandal attack in 1972, when the statue was damaged with a hammer. This unfortunate incident necessitated the placement of the Pietà behind bulletproof glass to ensure its safety. Nonetheless, the sculpture's expressive power remains undiminished, continuing to resonate with visitors through its timeless beauty and its profound message of redemption and hope.

Other works

Beyond Bernini's renowned Baldacchino and Michelangelo's Pietà, St. Peter's Basilica houses a vast array of invaluable artworks, enriching every corner of this sacred venue and contributing to its status as one of the most frequented sites during the Jubilee and throughout the year.

One of the most remarkable features within the basilica is the collection of mosaics that embellish the vaults, domes, and ceilings. These mosaics, crafted by some of the era's most celebrated artists, including Cavalier d'Arpino and Giovanni De Vecchi, depict various religious themes with a mastery that seamlessly blends art with devotion. The mosaic technique, chosen for its enduring longevity and radiance, permits these works to glow under the natural light filtering through countless windows, creating a visual spectacle of breathtaking beauty.

Among the standout sculptures, the funerary monument of Pope Urban VIII, crafted by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, is particularly noteworthy. Situated in the basilica’s choir, the monument is a majestic ensemble featuring the figure of the pope giving blessings, flanked by allegorical representations of Charity and Justice. This monument not only commemorates the impactful life of a pope who left a profound legacy in Church history, but also serves as a sublime testament to Bernini’s skill in transforming marble into figures imbued with profound emotion and rich symbolism.

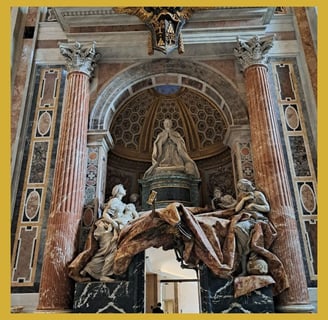

Equally striking is the funerary monument of Alexander VII, fashioned by Bernini during the twilight of his career. This intricate monument is decorated with allegorical figures that embody Truth, Prudence, Justice, and Charity, all revolving around the central figure of the pope in prayer. A particularly remarkable aspect of this monument is the representation of Death, crafted in black marble, which emerges from beneath a drapery to inscribe the pope's name on an urn, symbolizing the inexorable destiny of mankind.

Drop us a line

Follow us

Discover the Jubilee

Experience the Jubilee

Jubilee locations

Get ready for the Jubilee

Rome and the Jubilee